At-Will Employment in California: The General Rule

Section 2922 of the California Labor Code states: “An employment, having no specified term, may be terminated at the will of either party on notice to the other.” This provision underscores the at-will employment rule in California. At-will employment applies to jobs that do not specify a set duration; in other words, either the employer or employee can choose to end employment with proper notice. Employment is considered for a “specified term” only when the job’s duration is set for a period longer than one month.

Employers frequently depend on the at-will presumption to limit their liability, as this presumption allows them to justify terminations without providing a reason. However, this freedom to terminate employment is limited by several significant exceptions that prevent employers from acting against public policy.

The Public Policy Exception to At-Will Employment

While at-will employment allows terminations without a reason, it does not permit terminations that violate public policy. As determined in the California Supreme Court case Gantt v. Sentry Insurance (1992), an employer may not terminate an employee for reasons that are unlawful or that go against fundamental public policy. Public policy exceptions protect employees from being fired in situations where doing so would be harmful to society’s basic ethical standards.

For example, an employer cannot terminate an employee for reasons such as reporting unsafe working conditions, filing a workplace harassment claim, or participating in an investigation into discrimination. These actions are protected under public policy because they are essential for maintaining lawful and ethical work environments.

Statutory Exceptions to the At-Will Employment Rule

Various federal and state laws also establish strong exceptions to at-will employment by protecting employees from discrimination, retaliation, and unfair dismissal. Among these statutory protections are anti-discrimination laws and whistleblower protections, which shield employees from termination under specific circumstances:

- California Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA): This state law protects employees from discrimination based on characteristics like race, gender, age, disability, and religion.

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964: This federal law prevents discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin.

- Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA): This federal law prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities and requires reasonable accommodations in the workplace.

- Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA): This law protects workers aged 40 and older from discrimination based on age.

- Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA): This federal act allows eligible employees to take unpaid leave for medical and family-related reasons without fear of job loss.

- California Labor Code Section 1102.5 (Whistleblower Protection): This law prevents employers from retaliating against employees who report illegal actions or practices in the workplace.

These statutory protections ensure that employees are not subject to unjust termination in situations where their rights to a fair, safe, and discrimination-free workplace are at stake. Employees who believe they were wrongfully terminated in violation of one of these statutes can seek legal recourse against their employer.

The Common-Law Exception to California’s At-Will Employment Rule

In California, wrongful termination in violation of public policy is an established exception to the at-will employment rule. This principle, defined by common law, prevents employers from firing employees for reasons that conflict with fundamental societal values or laws. The leading case on this issue, Tameny v. Atlantic Richfield Co. (1980), set the standard, stating that an employer’s authority to terminate an at-will employee can be restricted by statutory requirements or by principles of public policy. This legal framework mandates that employers refrain from actions that would unlawfully or unjustly dismiss an employee.

Constructive Termination: When Working Conditions Are Unbearable

An employee may also claim wrongful termination if they were forced to quit due to intolerable working conditions created or permitted by the employer. This is known as “constructive termination.” According to Turner v. Anheuser-Busch, Inc. (1994), an employee must show that the employer either intentionally created or knowingly allowed unbearable conditions that would lead a reasonable person to feel they had no choice but to resign. In these cases, the employer’s actions are treated as a wrongful termination even though the employee technically quit.

What Counts as a Public Policy Violation?

For an employee to prove wrongful termination based on public policy, they must demonstrate that the termination violated a specific and significant public policy. In Stevenson v. Superior Court (1997) and Green v. Ralee Engineering Co. (1998), the courts outlined the requirements that a public policy must meet to qualify:

- Defined in Law: The policy must be explicitly stated in the state or federal constitution, laws, or regulations.

- Public Interest: The policy must serve the public good rather than just an individual’s interest.

- Well-Established: The policy must have been clearly recognized and established at the time of the termination.

- Substantial and Fundamental: The policy should be fundamental to the values and welfare of society.

For example, policies against discrimination, ensuring safe working conditions, and protecting employees who report illegal activity serve the public interest and would support a claim for wrongful termination if violated.

Proving the Connection Between Protected Activity and Termination

To successfully claim wrongful termination based on public policy, the employee must show a clear link—called a “causal nexus”—between their protected activity and the adverse employment action. In Turner v. Anheuser-Busch, Inc. (1994), the court held that evidence of a causal connection might include timing (such as if the termination occurs soon after the protected activity) or changes in the employer’s stated reasons for the termination. Additionally, an employer’s departure from its standard policies and procedures in handling the case can suggest retaliatory motives.

Without direct evidence, like a specific admission by the employer, employees often rely on circumstantial evidence to prove this nexus. Circumstantial evidence may include a rapid shift in the employer’s behavior, inconsistent reasons for the termination, or failure to follow established procedures.

Prerequisites for Filing a Tameny Claim: Understanding Wrongful Termination in Violation of Public Policy

In California, a Tameny claim, or a claim for wrongful termination in violation of public policy, allows employees to seek legal recourse if they were fired for reasons that go against fundamental societal values. However, certain prerequisites must be met for a Tameny claim to proceed. Here’s an outline of these essential requirements.

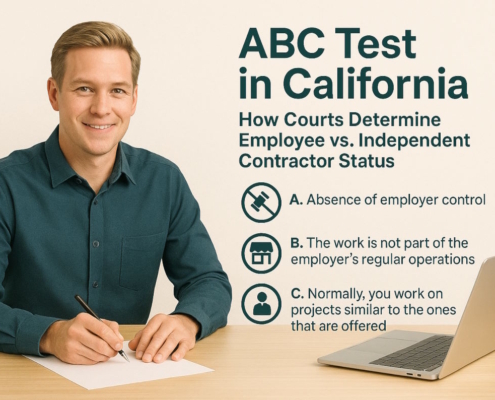

- Employer-Employee Relationship

A Tameny claim requires an actual employer-employee relationship. Independent contractors are excluded from this protection, as they do not meet the legal definition of an employee. The California cases Varisco v. Gateway Science & Engineering, Inc. (2008) and Ali v. L.A. Focus Publication (2003) confirm that only employees, not independent contractors, can pursue a wrongful termination claim under public policy.

Example: A freelance graphic designer cannot file a Tameny claim if their contract is ended, as they are not considered an employee under California law.

- Claim Limited to Employer, Not Co-Workers or Supervisors

A wrongful termination claim under Tameny can only be filed against the employer. The plaintiff cannot bring a Tameny claim against a co-worker or supervisor directly. In Khajavi v. Feather River Anesthesia Medical Group (2000), the court clarified this limitation, holding that only the employer is responsible for wrongful termination. However, certain other laws, such as California Government Code Section 12940, allow for co-workers or supervisors to be held liable for specific offenses, like discriminatory harassment or retaliation.

Example: If an employee is wrongfully terminated due to a supervisor’s actions, they must bring the Tameny claim against the employer itself, not the supervisor individually.

- Public Entities Are Exempt from Common Law Wrongful Termination Claims

Public entities, such as government agencies, are generally immune from common law claims, including wrongful termination under Tameny. This limitation means that public employees must rely on statutory claims instead. According to Government Code Section 815(a) and the case Ross v. San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (2007), public employees cannot pursue Tameny claims because these entities can only be held liable as specified by statute.

Example: A city worker who is terminated cannot file a Tameny claim against the city; instead, they must rely on specific statutory protections for their claim.

- Limitation on Claims Based on Statutory Violations with Established Remedies

In some cases, if a statute already specifies a remedy and procedure for a particular violation, that statute cannot serve as the basis for a Tameny claim. For instance, in Dutra v. Mercy Medical Center Mt. Shasta (2012), the court ruled that a plaintiff could not use Labor Code Section 132a as grounds for a Tameny claim, since violations of this section are exclusively within the jurisdiction of the Workers’ Compensation Appeals Board (WCAB). Allowing a Tameny claim in such cases would conflict with the remedies and procedures already defined by law.

Example: An employee fired after filing a workers’ compensation claim cannot use this fact alone to bring a Tameny claim because the workers’ compensation law has its own procedures for handling such issues.

Bases for claims of wrongful termination in violation of public policy

California’s public policy doctrine provides essential protections for employees against wrongful termination in situations where the employer’s actions conflict with key societal values. Below are some of the main bases for Tameny claims, or claims of wrongful termination in violation of public policy, supported by relevant cases.

- Discrimination and Retaliation Statutes

Claims of wrongful termination often arise from violations of anti-discrimination statutes. In Rojo v. Kliger (1990), the court ruled that the Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA) does not replace common law protections and that sex discrimination in employment can support a claim for wrongful discharge in violation of public policy. Additionally, disability discrimination may serve as a basis for such claims (City of Moorpark v. Superior Ct. (1998)).

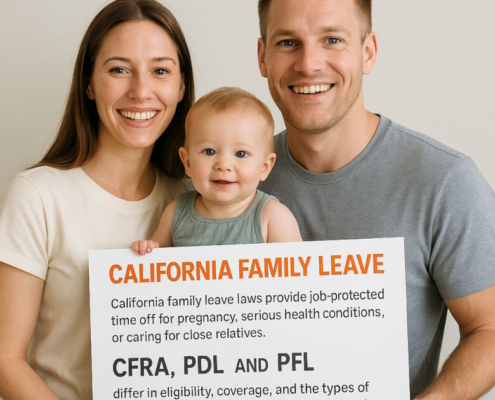

- Violation of the California Family Rights Act (CFRA)

The California Family Rights Act protects employees taking leave for family or medical reasons. Violating CFRA can be grounds for a wrongful termination claim. In Faust v. California Portland Cement Co. (2007), the court found that wrongful termination in violation of CFRA is actionable under public policy.

- Complaints About Workplace Safety (Cal-OSHA)

California’s Occupational Safety and Health Act (Cal-OSHA) protects employees who report unsafe working conditions. Boston v. Penny Lane Centers, Inc. (2009) held that employees could pursue wrongful discharge claims if terminated after raising workplace safety concerns. Similarly, Hentzel v. Singer Co. (1982) protected employees who report unsafe working conditions.

- Advocating for Appropriate Medical Care

The California Business and Professions Code protects physicians advocating for patients’ health care needs. Khajavi v. Feather River Anesthesia Med. Group (2000) recognized that retaliation against physicians advocating medically appropriate care violates public policy.

- Wage and Hour Complaints

Employees who report wage violations, such as unpaid overtime or withheld commissions, are protected. In Gould v. Maryland Sound Industries, Inc. (1995), the court found that termination to avoid paying owed wages or commissions could support a wrongful termination claim.

- Discussion of Wages

California Labor Code Section 232 protects employees who discuss their wages. Grant-Burton v. Covenant Care, Inc. (2002) held that firing an employee for wage discussions violates the right to discuss fair compensation, a matter of public interest.

- Testifying at a Hearing

Labor Code Section 230(b) protects employees who testify at legal hearings. In White v. Ultramar (1999), an employee alleged wrongful termination after testifying at an unemployment hearing, with the court ruling that such retaliation violates public policy.

- Political Activity

California Labor Code Section 1101 prohibits termination based on political activity. Ali v. L.A. Focus Publication (2003) upheld the right of employees to engage in political activities outside of work without risking their jobs.

- Penal Code Violations (e.g., Theft)

Employees reporting criminal activity, like theft, are protected under public policy. Casella v. SouthWest Dealer Services, Inc. (2007) held that the definition of theft under Penal Code Section 484 could be grounds for a wrongful termination claim.

- Fraud

Employees terminated for reporting fraud can file a wrongful discharge claim. Haney v. Aramark Uniform Services, Inc. (2004) found that public policy against fraud was sufficient grounds to support an employee’s wrongful termination claim.

- Tax Code and Anti-Trust Violations

Employees reporting financial misconduct, including tax evasion or kickbacks, are protected. Collier v. Superior Ct. (MCA, Inc.) (1991) recognized wrongful termination claims for employees fired after reporting such activities.

- False Claims Act Violations

California’s False Claims Act protects employees reporting government contract violations. Holmes v. General Dynamics Corp. (1993) held that retaliation for such reporting violated public policy, supporting wrongful termination claims.

- Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA)

The IRCA supports claims where employees report employers hiring undocumented workers. In Jie v. Liang Tai Knitwear Co. (2001), the court recognized this as a valid basis for a wrongful termination claim.

- Non-Compete Violations (Business and Professions Code Section 16600)

California law prohibits non-compete clauses as a condition of employment. D’sa v. Playhut, Inc. (2000) and Silguero v. Creteguard, Inc. (2010) held that firing an employee for refusing to sign or adhere to non-compete agreements violates the public policy favoring competition and mobility.

Why bring violation of public policy claims?

When an employee has been terminated in a way that violates state or federal laws, such as discrimination statutes, it may seem redundant to also bring a claim of wrongful termination in violation of public policy. However, including this additional claim can be highly strategic and beneficial for several reasons:

- Alternative Remedy When Administrative Deadlines Are Missed

If an employee fails to meet the required deadlines for administrative remedies—such as filing with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) or the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing (DFEH)—the public policy claim may be the employee’s only remaining option. This claim can proceed directly in court without the administrative prerequisites of statutory claims, providing a valuable remedy when others are unavailable.

Example: An employee misses the deadline to file a discrimination claim with the DFEH. They can still pursue a wrongful termination claim based on public policy to seek justice.

- Extended Statute of Limitations

In many cases, the statute of limitations (the time limit to bring a claim) for a wrongful termination in violation of public policy is longer than that of statutory claims. While discrimination claims often have shorter statutes of limitations, a public policy claim allows two years to file. This difference in timelines allows employees to bring a public policy claim even if statutory deadlines have passed.

Example: If an employee discovers they missed the deadline to bring a discrimination claim, they may still be able to file a wrongful termination claim under public policy within two years.

- Safeguard Against Erroneous Dismissal of Statutory Claims

In cases where the court may dismiss a statutory claim, a public policy claim serves as a backup, providing a different basis for the employee’s case. Should the court mistakenly reject a statutory claim, the wrongful termination claim remains, allowing the case to proceed.

Example: If a discrimination claim is dismissed due to a legal technicality, the public policy claim can still be used to present the wrongful termination argument at trial.

- Addressing Multiple Illegal Reasons for Termination

A wrongful termination in violation of public policy claim can be especially useful when an employee was terminated for a mix of illegal reasons. When multiple factors—such as discrimination, retaliation, or whistleblowing—contribute to the termination, proving each individual statutory claim may be challenging. With a public policy claim, the employee only needs to show that one or more illegal reasons likely influenced the termination for the claim to succeed.

Example: If an employee is terminated for a combination of age discrimination, wage complaints, and reporting unsafe work conditions, the public policy claim allows the jury to decide if any of these factors likely contributed to the termination.